What happens when you catch a wolf out mousing in Montana:

Posted in wolves, tagged gray wolf, Wolf on January 10, 2020|

Posted in Taxonomy, wolves, tagged coyote, coywolf, hybridization, Hybrids, Wolf on December 25, 2019|

An F1 cross between a gray wolf and a coyote that was produced through artificial insemination.

A few months ago, I wrote about a discovery that two species of howler monkey have evolved greater genetic divergence in a hybridization zone in southern Mexico. The hybrids were less fit to survive or reproduce, so natural selection has favored those individuals in both species that were genetically more divergent where their ranges overlap. This phenomenon, known as “reinforcement,” is a powerful tool that maintains both species as distinct.

I have been thinking about how this phenomenon may have played out in wolf evolution in North America. We have found that gray wolves across North America have at least some amount of coyote introgression, which has been revealed in several full genome comparisons.

The wolves that have most evidence of coyote introgression are those that live in areas that were not in the historic range of coyotes, while those with the least coyote introgression tend to be in the areas where gray wolves and coyotes were sympatric.

It is possible that something like reinforcement went on with wolves and coyotes living in the West. Hybrids between gray wolves and coyotes were probably less likely to be able to bring down large prey or were too large to live on small game, which is the staple diet of most Western coyotes. Over time, reinforcement through natural selection could have caused greater genetic differences between Western wolves and coyotes, and Eastern wolves were without coyote and thus never developed these greater genetic differences.

When coyotes came into the East, they mated with relict wolves, so that we now have whole populations of wolf with significant coyote ancestry.

Now, this idea is not one that I find entirely convincing. One is that ancient mitochrondrial DNA analysis from wolves in the East suggests they had coyote-like MtDNA, which, of course, leads to the idea that the wolves of the East were a distinct species.

Further, the discovery of the recent origins of the coyote makes all of this much more murky. Again, reinforcement is a process that is only just now being sussed out in the literature, and gray wolves and coyotes are unique in how much introgression exists between them. Their hybridization has essentially been documented across a continent. The only wolves that have no evidence of coyote ancestry live on the Queen Elizabeth Islands of the Canadian arctic. No coyotes have ever lived on these islands, so they have never introgressed into the wolf population.

The howler monkeys in the reinforcement study hybridize only along a narrow zone in the Mexican state of Tabasco. They are also much more genetically distinct than wolves and coyotes are. The monkeys diverged 3 million years ago, but the current estimate of when gray wolves and coyotes shared a common ancestor is around 50,000 years ago.

So gray wolf and coyote “speciation” is a lot more complex than the issues surrounding these monkeys.

But reinforcement is something to think about, even if it doesn’t fit the paradigm exactly.

Posted in German shepherd dog, Taxonomy, tagged german shepherd, German shepherd dog, gray wolf, Tomarchus, Wolf on May 23, 2019|

I love reading old breed books. Getting into German shepherds now means that I have a whole new selection of books to read, and in older German shepherd books that are written in English, there is a strong desire to distance this breed from wolves. At one time, the breed was banned in Australia because of its supposed wolf ancestry, and Australian sheep interests were quite concerned that the breed infuse wolf phenotype and behavior into dingoes if they got loose and crossbred. So there is a tendency to downplay any relationship between this breed and wolves, and this tendency sometimes gets quite ridiculous.

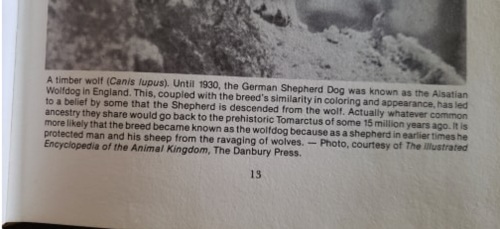

In the first few pages of Jane Bennett’s book on the breed, which had its last printed in 1982, I noticed this image of a wolf.

If you cannot read the full caption, check it out here:

So I don’t expect to see accurate zoology or paleontology in dog books, especially from old ones. And to be honest, I am skeptical that German shepherds are especially wolf-like dogs with close wolf-like ancestry. It is possible that some of the Thuringian sheepdogs in the breed’s ancestry had some wolf crossed in, but I don’t think they are wolfdogs in the same way that a Czechoslovakian vlcak is.

But the idea that the most recent common ancestor between a wolf and German shepherd was Tomarctus is not at all accurate. In some of the old dog books I have, Tomarctus is sometimes mentioned as an ancestor of modern dog species.

However, current paleontology places Tomarctus in the Borophagine subfamily of Canidae. Not a single living descendant of the Borophagine dogs exists. These dogs lived only in North America and all were extinct by the end of Pliocene. Tomarctus went extinct about 16 million years ago, which would be in the Miocene.

So it was not even a late surviving Borophagine dog, and it certainly was not the most recent common ancestor of wolves and German shepherds. If it were the most recent common ancestor, then Czechoslovakian vlcaks, Saarloos wolfhonden, and Volksoby would have been impossible to create. 15-16 million years is more than enough time for two mammalian lineages to lose chemical interfertility, and dogs and wolves simply are chemical interfertile right now.

The most recent common ancestor between a German shepherd and a wolf could have been a wolf kept at the Frankfurt zoo that some think is behind the Thuringian sheepdog Hektor Linksrhein/Horand von Grafrath, which is the foundation dog for the modern German shepherd breed. Or it could have been a wild wolf that mated with a sheepdog somewhere in Germany, and that sheepdog line got mixed into the breed. Further, dogs in Eurasia, some of which may have German shepherd in them, are interbreeding with wild wolves at a much higher frequency than we might have imagined.

I honestly don’t know, if the GSD breed has close wolf ancestry, and reasonable people can disagree on this issue. I have not seen definitely proof either way, so I do remain agnostic on this issue. The temperament of the breed, though, is of very trainable herding dog.

But whatever the truth is, I don’t think anyone thinks the most recent common ancestor of the German shepherd and the wolf was a species that outside the lineage of both.

This claim isn’t as bad as the claim that chow chows are derived from extinct digitigrade bears or from an extinct predatory species of red panda.

Jane Bennett’s book includes lots of good information in pedigrees and care of a German shepherd, but that page of the book indicates a strong desire to distance the dog from the wolf in a way that those of us living in the era of molecular biology and modern cladistics would find a bit bizarre.

The current thinking from full-genome comparisons is that all domestic dogs are derived from a now defunct lineage of Eurasian gray wolf. To keep Canis lupus monophyletic, we must keep the dog as part of that species.

So I have noticed a theme in many of these older books to keep German shepherds as distant from wolves as possible, even if it means making a claim that could easily disproved with a simple look at the Czechoslovakian vlcak or the Saarloos wolfhond, which both existed when this book was last printed.

Posted in deep thought, dog domestication, wild dogs, wolves, tagged coyote, dog domestication, dogs, Wolf, wolf persecution on April 6, 2019| 2 Comments »

Humans and the various canids belonging to gray wolf species complex possess the most complex relationship of any two beings currently living on this earth. At one point, they are our cherished companions, often closer to us than we ever could be with other people, and on another point, they are the reviled predators that might take a child in the night.

We have clearly defined relationships with other predators. Leopards and cougars, well, we might hunt them for sport or photograph them in the wild. But we never become closely aligned with them, except for those eccentrics who dare to keep such dangerous predators as pets.

People living in the Eurasian Pleistocene brought some wolves into their societies. Wolves and humans should have been competitors. We should have had the same relationship with each other as spotted hyenas and lions do in Africa now. But at some point, humans allowed wolves in.

Raymond Pierotti and Brandy Fogg demonstrate that many humans throughout the world have had some kind of relationship with wolves. In some cases, it is or was a hunting symbiosis. In others, they were totemic animals.

In their work, Pierotti and Fogg contend that the relationship between humans and wolves broke down with the rise of Christianity in the West. I don’t think that’s when it broke down. It started to become complex when humans began to herd sheep and goats.

In Kazakhstan, wolves are hunted and revered at the same time. The Kazakh people herd livestock, so they must always worry about wolf predation. Stephen Bodio documents this complex understanding of wolves in his The Hounds of Heaven.

“They hunt them, kill them, chase them with hounds and even eagles, take puppies and rear them live, identify with them, make war on them, and claim descent from them,” writes Bodio. This description sort of fits modern humanity’s entire relationship with this gray wolf complex. We pretty much have done and continue do almost all of these things.

Wolves, coyotes, and dingoes have killed people. So have domestic dogs. In the French countryside, wolf hunts were considered a necessity to protect human life, largely because has the longest and best documented history of wolves hunting people. The dispossession of rural peasants and the depletion of game in the forests created conditions where wolves would consider humans easy prey. Lots of European countries have similar stories. And when Europeans came to North America, they knew about the dangerous nature of wolves, even if they had never even seen one themselves.

Humans have declared war on wolves in Eurasia and in North America. The wolf is extirpated from much of its former range in Europe. They live only over a limited range in the lower 48 of the United States.

Man fought the coyote with the same venom and lead he threw at the wolf. The coyote’s flexible biology and social behavior meant that all that effort would come for naught. The coyotes got slaughtered, but they rebounded. And then some. And the excess coyote pups found new habitat opened up with big ol’ wolves gone, and they have conquered a continent, while we continue our flinging of lead and setting of traps.

In Victorian times, Western man elevated the domestic dog to levels not seen for a domestic animals. They became sentient servants, beloved friends, animals that deserve humanity’s best treatment.

And in the modern era, where fewer and fewer Westerners are having children, the dog has come to replace the child in the household. Billions of dollars are spent on dog accessories and food in the West. Large sectors of our agriculture are ultimately being used to feed our sacred creatures.

A vast cultural divide has come to the fore as humans realize that wolves and coyotes are the dog’s wild kin. Wolves have become avatars for wilderness and conservation, and coyotes have become the wolves you might see out your front window.

Millions of Americans want to see the wolf and the coyote protected in some way. Dogs of nature, that’s the way they see them.

The rancher and the big game hunter see both as robbers taking away a bit of their livelihood. Humans are lions. The canids are the spotted hyenas. And their only natural state is at enmity.

Mankind’s relationship to these beings is so strangely complex. It greatly mirrors our relationship towards each other. We can be loving and generous with members of our own species. We can also be racist and bigoted and hateful. We can make death camps as easily as we can make functioning welfare states.

And these animals relationships with each other are just as complex. Wolves usually kill dogs and coyotes they find roaming their territories. But sometimes, they don’t. Sometimes, they become friends, even mates. Hounds can be trained to run down a coyote, but sometimes, the coyote and the dog become lovers in the forest.

Social, opportunistic predators that exist at this level of success are going to be a series of contradictions. Dogs, wolves, and coyotes certainly are. And so are we.

It is what we both do. And always will.

Posted in wild dogs, wolves, tagged coyote, Wolf on January 16, 2018| 2 Comments »

Coyotes and anything that is called a wolf in North America are as genetically close to each other as we humans are to each other.

This is the most radical thing I’ve ever learned from a scientific paper.

The paper is about whether red wolves and Eastern wolves are hybrids, which is a controversial topic. They probably are hybrids, but what are they hybrids between?

Are they crosses between two really distinct species or are they hybrids between two lineages of what one might rather radically and boldly declare subspecies?

The really radical discovery of these genome-wide studies on wolves and coyotes in North America isn’t that red wolves and Eastern wolves are hybrids. The really radical discovery is that wolves and coyotes are much closer to each other than we assumed. The initial calculation suggested a divergence that happened only around 50,000 years ago.

Wolves in Yellowstone and Alaska have coyote genes, and coyotes in the Eastern US have wolf genes. That’s not a hybrid zone, which is what you get with bobcats and Canada lynx and with kit and swift foxes, where only a narrow hybrid zone has been identified.

Coyote and wolf genes have traveled across this continent, entering into what we have classically thought of as two distinct species but really aren’t.

My take is that coyote are nothing more than a diminutive wolf. Its ancestor was an archaic form of Eurasian Canis lupus, the Holarctic wolf. It wandered across the Bering Land Bridge during a warming period that happened roughly 50,000 years ago. It came into a continent that was already dominated by dire wolves, dholes, and archaic jackal-like canids, as well as a whole suite of large cats, including jaguars, American lions, sabertooths, and dirk-toothed cats.

The way to survive was not to be a large pack-hunter. That niche was already occupied by dire wolves and dholes, so they became convergently-evolved jackals.

A jackal evolved out of the wolf-lineage is a pretty durable animal, and it played second fiddle to the modern Holarctic wolves that invaded some 20,000 years ago. The wolves that came across were large wolves that were adapted to hunting larger prey, and as the dire wolf became extinct, the larger Holarctic wolf replaced the endemic North American wolf.

The behaviors of coyotes and wolves generally keeps them from interbreeding. Coyotes are much more strictly monogamous, a trait that would be of great importance for an animal that had to live on smaller prey species and carrion for survival.

Wolves are far less monogamous, and if prey populations are high, it is not impossible for wolf packs to have several females produce litters. These extra litters come from the female wolves that have not yet left their mother’s packs but have bred with wandering males that slip around at the edges of the established pack territories. These matings happen all the time in wolf societies, but generally, these females don’t get to raise their pups. They die of exposure or are killed by the main breeding female.

Western and Northern wolf packs kill interlopers. A coyote is nothing more than interloper and gets killed. The two animals could mate and produce fertile offspring, but they usually don’t.

But the wolves that colonized the Eastern forests developed differently. These Eastern forests had far more deer per square mile than the West, and greater social tolerance may have been a trait of these wolves, even when they were driven to near extinction. There is evidence that these wolves have mated with coyotes before European contact, but after European contact, they mated with the coyotes that came east.

The coyotes that came into the East were descendants of those little wolves that scrapped around the big predators of old. They could pack up as wolves to hunt deer, or they could remain in mated pairs to hunt only mice and rabbits. They could scavenge at the edges of human civilization, and they could thrive.

Most of North America is now under the reign of the little wolf, a remarkable feat of evolution.

Dr. Ian Malcolm’s most famous line from Jurassic Park is that “Life finds a way.” The context of the line is that he was rejecting the claim that the genetically engineered dinosaurs would never reproduce simply because they had chosen to engineer these creatures as solely female.

In our context, I would argue that “Wolves find a way.” Right now, the most successful wolf lineage in the world is the one that includes domestic dogs and dingoes. They are found on every continent, except Antarctica, and were found there until very recently. This lineage does well because it has become part of humanity. Populations go feral or go stray. Others become so humanized that they almost cease to be an entity separate from our species. It has largely given up hunting big game for survival and thrives on the fat of human civilization.

In North America, the second most successful wolf lineage is this coyote lineage. It thrives because it can much more easily exploit life in the civilized world than the larger, more specialized wolves. They can scavenge. They can mouse and rabbit. They can run deer. They can eat apples and pears in orchards. But they do not depend upon the large ungulates for survival.

It is a wolf that cane become a jackal, then a fox, and then, should the deer numbers be high enough, return to a more lupine existence as a pack hunter.

Yes, my concept of the coyote and the North American wolf means rejecting some fossils. There are fossils that have been described as “coyotes” that date to 1 million years before present.

But the full-genome comparisons are so compelling that I have to reject these fossils. The full genome comparisons are exactly like the ones that have been used to compare humans to chimps, humans to gorillas, and domestic cats to tigers (and cats).

The findings of these studies aren’t as controversial as the wolf and coyote genome comparisons have been, but that’s because they haven’t found that certain endangered species are likely hybrids.

The red wolf and Eastern wolf exponents can debate as to whether these animals are hybrids or not, but the real problem is the discovery of recent divergence between the wolf and coyote.

This recent divergence allows for a hybrid origin for the red wolf and Eastern wolf, but it also shows that this hybrid origin is most a debate of semantics. They might be hybrids, but they are hybrids between two different forms of the same species. And the resulting hybrids are much better adapted to living in the new North America.

That’s the best case red wolves and Eastern wolves have in light of the genetic data.

Paleontology is often the study of bones and teeth and comparing bones and teeth. Except for instances in which ancient DNA has been extracted and compared, most of these studies will miss very important parts of an organism’s natural history. Because of recombination, DNA studies can also be flawed, but they are a much more complete record of an organism’s evolution than we might get from measuring bones.

And we know now that canids are particularly prone to parallel evolution. The golden jackal species as classically defined has had to be split into two. African golden jackals are much more closely related to Eurasian wolves, while Eurasian golden jackals are much more distinct lineage. Their similarities are the result of parallel evolution, which was also at work in producing the jackal-like coyote out of the wolf lineage.

Had their bones been found in some ancient layer of sediment, paleontologists using comparative morphology methods would have declared them all one species, an error that is likely been repeated thousands of times with any number of specimens from a variety of lineages.

I like paleontology, but every time I read a paper from that discipline, I wonder if this is the full story.

And pretty sure virtually every paleontologist does too.

If the full-genome comparisons are correct– and I have little reason to think they are wrong–then we are living in the reign of the little wolves. They press on deeper into Alaska and Canada. They push east until they hit every state. They pushed deep into Central America, now running the right at the edge of the Darien Gap. Once they cross that great swamp, they will arrive in Colombia and will be the first wild Canis species to cross into South America since the dire wolf.

It’s just a matter of time. They will make it.

And South America’s guild of unique canid species are in for some disruption.

I hope they can handle our little renegade, for the reign of the little wolf could also displace the fruit-eating wolf with a mane and the short-legged convergent dhole.

Those problems are a way off, but they are worth thinking about, as the coyote completes its conquest of one continent and reaches for another.

Posted in wild dogs, wolves, tagged Canis lupus pallipes, India, Indian wolf, Wolf on December 11, 2016| 5 Comments »

This is now playing on Netflix:

These wolves really do remind me of coyotes, right down to their consumption of fruit when it’s available.

Posted in wild dogs, wolves, tagged coyote, Eastern coyote, Eastern wolf, gray wolf, grey wolf, red wolf, timber wolf, Wolf on August 1, 2016| 5 Comments »

I’m currently reading John Lane’s excellent book, Coyote Settles the South. It is an excellent book, and I will be reviewing it here very soon. The whole time I’ve been reading it I thinking about my encounter with the male Eastern coyote I called in back in March.

He’s not exactly the same coyote that Lane is writing about. He’s a coyote of the gray woods, not the subtropical pine forests and river bottoms.

But in some ways, he is the same. He is the same creature that has adjusted to all that Western man can throw at him and thrived.

And he’s thrived at the expense of the wolves that once roamed over the Northeastern US and the South. He’s just the right size to live on a diet of rodents and rabbits but also has the ability to pack up and hunt deer. He can be an omnivore, enjoying wild apples and pears that fall to the ground, almost as much as he would if he came across a winter-killed deer.

The coyote is a survivor. I’ve written on this space several times that the reason he has thrived is because he has been here far longer than the wolves that once harried his kind. Until last week, it was assumed that the coyote split from the wolf some 1 million years ago. This million year split has been used for virtually every study that has examined the relationships between different populations or species in the genus Canis. It is used to set the molecular clock so that we can figure out when wolves and dogs split and perhaps give us some idea as to when dogs may have been domesticated.

This assumption has been directly challenged in a new study that was released in Science Advances last week. The paper examined full genome sequences of several different canids, and it can be argued that it pretty much ended the debate as to whether the red wolf and Eastern wolf are species. They aren’t. Instead, they are the result of hybridization between wolves and coyotes. Most of the media attention has paid attention to this discovery in the study.

It’s the most important practical implications, because the US Fish and Wildlife Service delisted the gray or Holarctic wolf in most of the Eastern, Southern, and Midwestern states in favor of protecting the Eastern and red wolves. Red wolves are called Canis rufus, and Eastern wolf is Canis lycaon. With them being recognized as hybrids, this greatly complicates the issue of how to conserve them under the Endangered Species Act, which, as its name suggests, is meant to conserve actual species and not hybrids between species.

The authors of the study feel that these hybrid populations are still worth conserving, largely because the red wolf contains the last reservoir of genes belonging to the now extinct wolves of the Southeast.

But in order to make this work, we’re probably going to have to rewrite the Endangered Species Act, and that is not going to happen any time soon.

However, the finding in the study that is worth discussing more is that not only showed that red and Eastern wolves were not some relict ancient species of wolf. It is the finding that coyotes and wolves split only 50,000 years ago.

Using a simple isolation model and a summary likelihood approach, we estimated a Eurasian gray wolf–coyote divergence time of T = 0.38 N generations (95% confidence interval, 0.376 to 0.386 N), where N is the effective population size. If we assume a generation time of 3 years, and an effective population size of 45,000 (24, 25), then this corresponds to a divergence time of 50.8 to 52.1 thousand years ago (ka), roughly the same as previous estimates of the divergence time of extant gray wolves.

This finding means that the studies that use that 1 million year divergence time to set the molecular clock for all those dog domestication studies need to be reworked. This is going to have some effect on how we think about dog domestication, and although the domestication dates have been moved back in recent years, the actual split between dogs and wolves is likely to be much later than when we see the first signs of domestication in subfossil canids.

That’s one important finding that comes from this discovery that wolves and coyotes are much more closely related.

The other is that yes, it did pretty much end Canis rufus and Canis lycaon as actual species, but it probably also ends the validity of Canis latrans as a valid species. Coyotes could be classified as a subspecies of wolf. Indeed, they are much more closely related to wolves than Old World red foxes are to New World red foxes, which split 4oo,ooo years ago. And there is still some debate as to whether these two foxes are distinct species, because we’ve traditionally classified them as a single species. Plus, if we start splitting them into two species, we’re likely to find the same thing exists with least weasels living in the Old and New World. And the same thing with stoats.

And then it’s not long we’re fighting over the house mouse species complex.

But if we’re going to lump red foxes, it’s pretty hard not to lump coyotes and wolves. It is true that wolves normally kill coyotes in their territory, but it also found that wolves in Alsaska and Yellowstone, wolves that were thought to be entirely free of any New World ancestry, also had some coyote genes.

So the coyote, like the extinct Honshu wolf and the current Arabian wolf, could be correctly thought of a small subspecies of wolf. We know from paleontology that in both North America and Eurasia there were various forms of canid that varied from jackal-like to wolf-like, and although we know the jackal-like form is the earliest form, these two types have ebbed and flowed across Eurasia and North America. We’ve assumed that the jackal-like forms gave became the coyote and the larger wolf-like forms have become the gray, red, and dire wolves.

But what we’re looking at now is the coyote isn’t the ancient species we thought it was. It’s very likely that some ancestral wolf population came into North America, and instead assuming the pack-hunting behavior of Eurasian wolves, it tended toward the behavior of a golden jackal. When this ancient wolf walked into North America, it would have found that the pack-hunting niche was already occupied by dire wolves. There were many other large predators around as well, and evolving to the jackal-like niche would have made a lot more sense in evolutionary terms.

This is what the coyote is.

The pack-hunting modern wolf came into the continent and took it by storm, and the coyote exchanged genes with it. They lived together as sort of species-like populations in the West, but when wolves became rare from persecution following European settlement, the coyote and wolf began to exchange genes much more.

So with one study using complete genomes, the entire taxonomy of North American Canis is truly blown asunder.

And the implications for dog domestication studies and for the practical application of the Endangered Species Act could not be any more consequential.

Very rarely do you get studies like this one.

It changes so much, and the question about what a coyote is has become unusually unsettling but also oddly amazing.

I will never think of a coyote the same way.

The mystery is even more mysterious.

Posted in Uncategorized, wild dogs, wolves, tagged Denali National Park, East Fork wolf pack, The Wolves of Mt. McKinley, Wolf, wolves on July 14, 2016| 2 Comments »

Any time someone from the Lower 48 goes to Alaska, the instant question that comes up on return is the traveler encountered a wolf.

The answer for me is simply no, and I knew fully well there were very low odds of me seeing a wolf. I live where there are tons of coyotes, and I see one about every six months. They are very good at keeping themselves hidden from people, and from what I’ve read about wild wolves, it is even more true about wolves.

Some members of my family went to the Kroschel Wildlife Center and saw a tame wolf named Isis. (I was told that she would not stop howling during their entire visit!).

My best chance at seeing a wild wolf was at Denali, but there is a catch to that story.

Denali National Park is roughly the size of Massachusetts. It’s full of moose, Dall sheep, caribou, beaver, and porcupines.

You’d think that place would be full of wolves, but it’s not.

In fact, a place that size really can’t hold as many wolves as it does wolf prey. Because wolves are top predators, they just can’t exist in such large numbers, and that fact is true regardless if you’re talking about wolves in Denali, cheetahs in Namibia, or lions in the Gir Forest.

So even in the best of times, there would always be just a few wolves roaming the park. They would be laid on pretty thinly on the land.

But these are not the best of times for wolves in Denali.

The traditional “buffers” that have been set up near the park that prevented legal wolf hunting and trapping near the park were lifted in 2010, and the wolf population went from 147 wolves in 2007 to 49 wolves in 2015.

49 wolves over a land the size of Massachusetts.

49 is still more than the number of wolves living in actual Massachusetts, which may be 0 wolves. It may not be, though. One was killed in Massachusetts in 2008, and one or two could be lurking somewhere in the Berkshires, where they may mistaken for big coyotes.

But 49 is roughly a third of what the population was nearly a decade ago. My chances of seeing a wolf in Denali were 45 percent in 2010. They were 5 percent in 2015.

One of the best things I did at the park was take a hiking nature tour. My tour guide was very well-informed about wolf issues, and she told us about a wolf following one of her tour groups. There was no fear involved, but when someone in the party pointed out that a wolf was following them, she was certain it was a dog. She was very surprised to see that it was a wolf, and it was close.

The wolf ran off, of course.

But she also told the story of what happened to the East Fork wolf pack. This is the famous wolf pack that Adolph Murie studied. They were the wolves that were featured prominently in The Wolves of Mt. McKinley. This was the pack to which Wags, Murie’s tame wolf belonged.

Right now, the pack exists as only a single female. Her mate was killed on state land near the park entrance. She also had a litter, but I’ve not been able to find out what exactly happened to them. (I was there just a few days after this story came out on Alaska NPR).

I understand that Alaska has to balance interests between outfitters, who want predator control and liberal predator hunting allowances, and the desire of the American people to have relatively intact ecosystems in our national parks.

I get it.

I get that Canis lupus isn’t an endangered species worldwide, and it certainly isn’t an endangered species in Alaska, where the species is still going strong.

But it seems just a little perverse that we cannot maintain those buffers once again. I came thousands of miles to see wilderness where wolves might be.

I am okay with knowing they might be. I don’t have to see them. I just need to know they are there.

We had a small enough tour group that the guide and I got to talk about wolves a bit. She talked about her cocker spaniel and how that dog was far more rugged than she looked. The dog had been on many back country trips, and she wondered how closely related her spaniel was to those wolves.

Pretty close.

But still far enough away.

Posted in Carnivorans, wild dogs, wildlife, wolves, tagged sea otter, Wolf on June 2, 2016| 1 Comment »