Unlike the somewhat problematic aquatic ape theory, what I’m about to propose really isn’t that controversial at all.

The acquatic ape theory (more correctly called “the aquatic ape hypothesis”) argues that it was living in and near the water that forced humans to evolve bipedalism and is also used to explain why we have fat under our skin and like to swim. It’s even used as a possible reason why we have little fur left on our bodies, and it also claims that humans are unique among primates in our ability to hold our breaths under water, which isn’t actually true.

This hypothesis contends that humans were on our way to becoming marine mammals, and that this has made all the difference.

I don’t buy it.

But I do think something like this has happened with another animal that we currently don’t regard as being a “marine mammal.”

I’m talking about retrievers.

Now, we usually don’t think of them as being marine mammals. They are, after all, just a subset of domestic dogs, which are themselves a subspecies of the common wolf, Canis lupus familiaris.

But unlike other dogs and wolves, the retriever is somewhat better adapted to swimming and diving than other dogs.

All dogs have connective tissue between their toes, but in retrievers, this connective tissue is a bit more extensive, which certainly gives them some advantage in swimming. All dogs are web-footed, but retrievers are more web-footed than others.

Many Labrador retrievers and some golden retrievers also have a tendency to put on quite a bit of fat. This is usually attributed to the dogs being derived from St. John’s water dogs that had to have voracious appetites to survive on Newfoundland during the winter when they weren’t used on the fishing fleet.

But such a tendency toward obesity doesn’t exist in arctic breeds, including those from Labrador and Greenland, which were similarly left to roam and forage when not being used for work. These dogs have healthy appetites. but you very rarely hear of a fat one.

But in Labrador retrievers, being fat is almost a breed characteristic. In the UK breed ring, the Kennel Club has had to crack down on people showing fat Labradors in the ring, for there are a great many dog judges in that country who think that a Lab shows ‘good bone’ when he’s shaped like a jiggling barrel.

This tendency towards being fat, though, does have an advantage for a dog that spends a lot of time in cold water. Fat insulates. It is also quite buoyant.

One can see that nature would have selected for St. John ‘s water that would have been more likely to have put on fat as a way of being able to handle swimming long distances in cold water. The fat would make the dog float more, and the animal would be able to keep its head above water with less effort. And the fat would insulate it a bit more.

And although both of these features would be marginally advantageous, they would still have real consequences with a working water dog.

Before the St. John’s water dog developed, the European water dog was poodle-type animal. It had a very thick coat that protected the animal from the worst of the cold, but the coat also had a tendency to collect water. It was also a source of drag that slowed the animal down when it swam.

The clips we see in Portuguese water dogs and poodles stem from attempts to reduce drag while still keeping the protective coat.

The St. John’s water dog was different from all these European water dogs in that it had a smooth coat.

It was actually selected for this coat; any dogs that were born with feathering were shipped off to Europe.

A smooth coat has certain advantageous for a marine mammal.

After all, have you ever seen a seal with poodle fur?

What about a long-haired otter?

These animals have very close coats because this makes the animal move more efficiently through the water.

To have a water dog with an otter’s coat would have meant that clipping was no longer necessary. The dense undercoat and the fat would have provided enough protection against the cold water, and the smooth coat required no maintenance. And the dog could swim longer and harder in very cold water for much longer.

The St. John’s water dog was dog on its way to becoming a marine mammal.

Indeed, if we now count polar bears a marine mammals, maybe we should classify this extinct breed of dog as one, too.

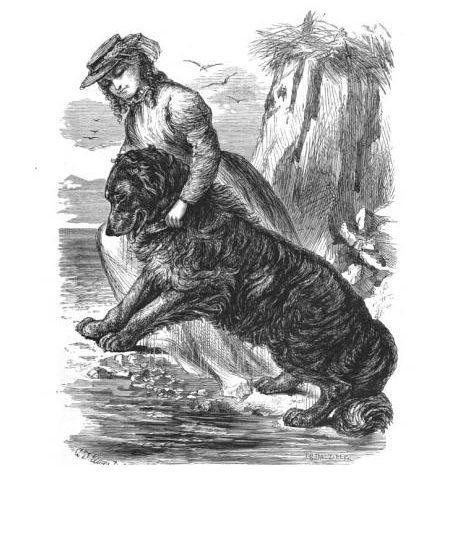

There are accounts of these dogs swimming for days at sea, which might be exaggerations, and stories of them diving many feet to retrieve shot seals. There are even some fellows who use the dogs to pursue shot porpoises with varying degrees of success. They were also use to retrieve shot waterfowl and sea birds from those very same seas, which is sort of the same work their descendants do today.

But they were most famous for retrieving fish off of lines. In the old days, the English fishermen from the West Country would come to Newfoundland to fish with hooked lines. They plied the waters in small dories, and they would send their dogs to help haul in the lines. In those days, the fishhooks often were not barbed, and when the dog came upon the hooked fish, there was a good chance that it could escape. A good dog could catch the cod if it managed to work its way off the hook at the last minute, which is not an easy task!

Most retrievers and the modern Newfoundland and Landseer breeds derive from this water dog. Some strains are very well-adapted to swimming in cold water. Others less so.

The retrievers of the United Kingdom were used primarily on shooting estates, where land-based game birds and lagomorphs were their main quarry. Some were used to retrieve waterfowl, but the British retriever culture was primarily that of a land-based working dog. Over time, they bred for a smaller and lither working dog, which still shows up in the strains of golden retriever that are primarily bred for work. During the heyday of the working flat-coated retriever (of which the golden retriever is a surviving remnant), the majority of these dogs were 50-60-pound dogs with longer legs and gracile frames– quite different indeed from the somewhat robust water dogs of Newfoundland from which they descended.

If the particular shore-fishing culture of Newfoundland had been allowed to continue on for many, many centuries, it is likely that the the St. John’s water dog really would have begun to have evolved through both natural and artificial selection into a much more marine-adapted animal than it was. Perhaps the would have evolved even more webbing between their toes. Maybe they would have actually evolved a real layer of blubber beneath their skins for insulation.

At least one species of wild dog is semiaquatic. The short-eared dog of South America has been little studied, but in most analyses of its diet show that it eats a lot of fish. The short-eared dog has very webbed feet— even more so than modern retrievers do. Because they live in Amazonia, they have no need for fat for insulation, but it has been suggested that this webbing is an adaptation that helps the dog pursue a more aquatic existence than other South American wild dogs.

St. John’s water dogs were famous for their fishing abilities, and they were well-known for charging into the surf and coming out with a fish, a feat that one sometimes sees retrievers doing quite well. One could see that over time, that the St. John’s breed would have evolved even more in this direction than the short-eared dog has.

But the Newfoundland fishing changed over time. Better hooks and mechanized fishing equipment made the dogs largely obsolete. The cod fishery has collapsed, as has the fishery for almost everything else. The outports of Newfoundland were shut down through resettlement schemes.

And the ancestral bloodlines of the St. John’s water dog became polluted with “improved” Labrador retriever blood from UK and the North American mainland. The last of the St. John’s water dogs with no Labrador retriever ancestry are believed to have died in the 1970’s.

In the US, Labrador retrievers are called “duck dogs,” but virtually no Labrador retriever that is being used as a hunting dog in the US today is used exclusively on waterfowl. Most of them at least moonlight as flushers and retrievers land-based game birds, which usually have longer seasons and more liberal bag quotas.

The retriever has to be a spaniel a lot of the time.

In the UK, the retriever is still primarily used on land-based game, though they are still used in “wildfowling” (a nice word for duck hunting).

In no place is it required to be the same kind of water dog that its ancestors were.

The potential for it evolving into a canine marine mammal has long sense passed.

But it could have gone down this road.

The retrievers that exist today are gun dogs that have been built and selected out of this lineage.

And it’s really what makes them unique as working dogs.

Now, this all might sound a bit bizarre, but this summer, reader Mashka Petropolskaya sent me this master’s thesis on the behavior of Labrador retrievers in an aquatic environment. The thesis was written by a student in the marine sciences program at the University of Porto in Portugal, and the thesis found that Labrador retrievers are unusually attracted to water and that access to water and swimming opportunities may be very important for the welfare of dogs in that breed.

Not all Labradors like the water, but there clearly is a tendency in retrievers to be interested in the water.

So maybe we really need to appreciate their “marine mammal” tendencies more in order to provide them the best environment possible.

Read Full Post »