Very interesting concepts:

Posted in dog domestication, tagged dog domestication, Raymond Pierotti on April 28, 2018| 4 Comments »

Posted in West Virginia, tagged Don Blankenship, feral horse, West Virginia on April 22, 2018|

Feral horses run in the wiry grass of Don Blankenship’s prairies. Once real mountains stood here, all crowned in ash and oak and hickory, but beneath them was a black rock. Over the centuries, men came and dug at the earth and sweated and died and then the bulldozers came and the mountains were gone. The state demanded that the coal operators do something to reclaim the land, so they planted some cheap grass and a couple of pine trees. But the land was forever changed.

Over the years, the jobs all went away, and those who had a few pleasure horses took them to the new grasslands and set them free. Better to be “wild horses” on the range than dog food was the simple logic.

And the stallions round their mares in this new steppeland. They nicker and fight the wars of that ancient Equus lambei, which a few romantics like to hope gives some sort of license to the native status of the modern horse on this continent.

At the same time, the state of West Virginia is trying its hand at restoring elk to these very same prairie lands. The elk were natives of the Eastern forests, and the ones being turned out onto these ranges are from Kentucky and Arizona. And those of Kentucky are still of the Rocky Mountain form of elk, not the long gone Eastern kind, which may now exist only in the muddled genetics of some New Zealand ranched herds.

The elk need the grass too, and worries are the horses will make the range too bare. And the elk will not make a comeback.

But the truth of the matter is neither species is native to land that never existed before. The glaciers never made it this far south, and the steepness of the terrain before the dozers came is testament to the antiquity of these mountains. They once stood like the Rockies or the Himalayas, but the millennia of erosion wore them down until the coal operators showed up to cut down their remnant. The glaciers never smoothed out the mountains, but human greed certainly did.

Meanwhile, Don Blankenship is back in politics. He is a former coal operator, a greedy, nasty one at that, the kind that was once excoriated in all those old union songs, but now as the mines employ fewer and fewer workers and UMWA is all broken and busted, he plays the working class victim. All railroaded by “union bosses” and Obama, he didn’t do anything wrong, he tells the gullible.

He’s thrown his hat into the US Senate race. His ads call all his opponents liberals and abortion lovers. He plays up his conspiracy theory about Obama having it out for him. He feigns tears about Indiana bats that are being killed by windmills.

He says he’ll drain the swamp. Maybe, he will, but I have the idea that he might just fill it up with coal slurry. That’s what happened to poor Martin County, Kentucky. Blankenship was CEO when his company’s slurry impoundment overflowed and filled up the Tug Fork River.

He sells the false hope that if you just get rid of a few more environmental and labor regulations, the coal industry will come roaring back. He also says that if we just build Old Man Trump’s wall on the Mexican border, we won’t have any more problems with drugs. After all, the drug problem must surely come from brown foreigners, and not the pharmaceutical industry and those totally unscrupulous doctors who prescribed opioids for every little discomfort.

The politics he offers are the politics of the apocalypse. In land where no real hope can be found, a little false hope will do.

And the miners lose their jobs and their homes and their pleasure horses join the ranks of the feral bands.

The Bible talks about the four horsemen of the apocalypse, but in West Virginia, the hoofbeats of that sound the impending doom have no riders at all.

They are the roving bands of the abandoned, left out to sort out a new existence on Don Blankeship’s prairies.

The snakeoil of politicians rings out on the airwaves, and every year, new horses get turned out, and the mares drop their feral foals.

The coal company’s rangeland gets denuded a little bit more, and the elk might not stand much of a chance.

In this apocalypse, death will come. Sooner or later, the horses will starve on those pastures. A few good souls might get some of them adopted, but most will either starve or wind up shot.

Perhaps, this election will be the final burlesque of Blankenship, but he’s not the only coal country caudillo in West Virginia. The current governor is a more successful sort of politico of this stripe, and the legislature if full of people like him. The long suffering of the people will go on and on, and the horses will continue to be turned out into the wild,

Already, coal towns are advertising their “wild horses” as an attraction draw tourism. It’s a more benign falsehood than the one Blankenship is offering.

But it is not so benign for the horses or the coming elk. For them, the apocalypse is coming. They cannot know it, for if they did, they would run.

And their hoofbeats would ring out the warning of our impending doom.

Posted in dog domestication, Uncategorized, wild dogs, tagged black-backed jackals, cheetah, dog domestication, Randall L. Eaton on April 8, 2018| 4 Comments »

We think of interactions between predators as always antagonistic. Meat is hard to come by, and if one comes by meat on the hoof, it is unlikely that the owner-operator of said flesh will give it up willingly. Meat is a prized food source, and it is little wonder that most predators spend quite a bit of energy driving out competitors from hunting grounds.

Because of this antagonism, the domestication of wolves by ancient hunter-gatherers is difficult to explain. Indeed, the general way of getting wolves associated with people is see them as scavengers that gradually evolved to fear our species less.

This idea is pretty heavily promoted in the dog domestication literature, for it is difficult for experts to see how wolves could have been brought into the human fold any other way.

But there are still writers out there who posit a somewhat different course for dog domestication. Their main contentions are that scavengers don’t typically endear themselves to those from which they are robbing, and further, the hunter-gatherers of the Pleistocene did not produce enough waste to maintain a scavenging population of wolves.

It is virtually impossible to recreate the conditions in which some wolves hooked up with people. With the exception of those living on the some the Queen Elizabeth Islands, every extant wolf population has been persecuted heavily by man. Wolves generally avoid people, and there has been a selection pressure through our centuries of heavy hunting for wolves to have extreme fear and reactivity. It is unlikely that the wolves that were first encountered on the Mammoth Steppe were shy and retiring creatures. They would have been like the unpersecuted wolves of Ellesmere, often approaching humans with bold curiosity.

As I have noted in an earlier post, those Ellesmere wolves are an important population that have important clues to how dog domestication might have happened, but the truth of the matter is that no analogous population of wolves or other wild canids exists in which cooperation with humans is a major part of the survival strategy. The wolves on Ellesmere are not fed by anyone, but they don’t rely upon people for anything.

But they are still curious about our species, and their behavior is so tantalizing. Yet it is missing that cooperative analogy that might help us understand more.

I’ve searched the literature for this analogy. I’ve come up short every time. The much-celebrated cooperation between American badgers and coyotes is still quite controversial, and most experts now don’t believe the two species cooperate. Instead, they think the badger goes digging for ground squirrels, and the coyote stand outside the burrow entrance waiting for the prey to bolt out as the badger’s digging approaches its innermost hiding place in the den. The coyote gets the squirrel, and the badger wastes energy on its digging.

But there is a story that is hard to dispute. It has only been recorded once, but it is so tantalizing that I cannot ignore it.

Randall Eaton observed some rather unusual behavior between black-backed jackals and cheetahs in Nairobi National Park in 1966.

Both of these species do engage in cooperative hunting behavior. Black-backed jackals often work together to hunt gazelles and other small antelope, and they are well-known to work together to kill Cape fur seal pups on Namibia’s Skeleton Coast. Male cheetahs form coalitions that work together to defend territory and to hunt cooperatively.

However, the two species generally have a hostile relationship. Cheetahs do occasionally prey upon black-backed jackals, and black-backed jackals will often mob a cheetah after it has made a kill, in hopes of forcing the cat to abandon all that meat.

So these animals usually cannot stand each other, and their interactions are not roseate in the least. Eaton described the “normal interaction” as follows:

The normal interaction between these two predators occurs when the jackals hunt in the late afternoon and come into a group of cheetahs. The jackals, often four or five, are normally spread out over several hundred yards and maintain contact by barking as they move. When cheetahs are encountered by one of the jackals, it barks to the others and they all come to the cheetahs, sniffing the air as they approach apparently looking for a kill. If the cheetahs are not on a kill, the jackals search the immediate area looking for a carcass that might have just been left by the cheetahs. If nothing is found, they remain near the cheetahs for some time, following them as they move ; and when a kill is made the jackals feed on the leftover carcass. If the cheetahs have already fed and are inactive and if a carcass is not found nearby, the jackals move on.

However, Eaton discovered that one particular group of jackals and one female cheetah had developed a different strategy:

At the time I was there in November, 1966, one area of the park was often frequented by a female cheetah with four cubs and was also the territory of a pair of jackals with three pups. The jackal young remained at the den while the adults hunted either singly or together. Upon encountering the cheetah family, the jackals approached to about 20 yards and barked but were ignored except for an occasional chase by the cubs. The jackals ran back and forth barking between the cheetahs and a herd of Grant’s gazelles (Gazella granti) feeding nearby. The two jackals had gone on to hunt and were almost out of sight by the time the adult cheetah attacked two male Grant’s gazelles that had grazed away from the herd. The hunt was not successful. The jackals took notice of the chase and returned to look for a kill ; it appeared that they associated food with the presence of the cheetahs and perhaps with the chase.

One month later, while observing the same cheetah family, I noticed that the entire jackal family was hunting as a group. The cheetah and her cubs were about 300 yards from a herd of mixed species. This same herd had earlier spotted the cheetahs and given alarm calls. The adult cheetah was too far away for an attack,there was little or no stalking cover and the herd was aware of her presence. The cheetahs had been lying in the shade for about one-half an hour since the herd spotted them when the jackals arrived. Upon discovering the cheetahs lying under an Acacia tree, one of the adult jackals barked until the others were congregated around the cheetah family. The jackal that had found the cheetahs crawled to within ten feet of the adult cheetah which did not respond. The jackal then stood up and made a very pneumatic sound by forcing air out of the lungs in short staccato bursts. This same jackal turned towards the game herd, ran to it and, upon reaching it, ran back and forth barking. The individuals of the herd watched the jackal intently. The cheetah sat up and watched the herd as soon as it became preoccupied with the activity of the jackal. Then the cheetah quickly got up and ran at half-speed toward the herd, getting to within 100 yards before being seen by the herd. The prey animals then took flight while the cheetah pursued an impala at full speed.

Upon catching the impala and making the kill, the cheetah called to its cubs to come and eat. After the cheetahs had eaten their fill and moved away from the carcass, the waiting jackals then fed on the remains.

Eaton made several observations of this jackal family working with this female cheetah, and by his calculations, the cheetah was twice as successful when the jackals harassed the herds to aid her stalk.

Eaton made note of this behavior and speculated that this sort of cooperative hunting could have been what facilitated dog domestication:

If cheetah and jackal can learn to hunt mutually then it is to be expected that man’s presence for hundreds, of thousands of years in areas with scavenging canines would have led to cooperative hunting between the two. In fact, it is hard to believe otherwise. It is equally possible that it was man who scavenged the canid and thereby established a symbiosis. Perhaps this symbiosis facilitated the learning of effective social hunting by hominids. Selection may have favored just such an inter-specific cooperation.

Agriculture probably ended the importance of hunting as the binding force between man and dog and sponsored the more intensive artificial selection of breeds for various uses. It is possible that until this period men lived closely with canids that in fossil form are indistinguishable from wild stock (Zeuner, 1954).

Domestication may have occurred through both hunting symbiosis and agricultural life; however, a hunting relationship probably led to the first domestication. Fossil evidence may eventually reconstruct behavioral associations between early man and canids.

Wolves are much more social and much more skilled as cooperative hunters than black-backed jackals are. Humans have a complex language and a culture through which techniques and technology can be passed from generation to generation.

So it is possible that a hunting relationship between man and wolf in the Paleolithic could have been maintained over many generations.

The cheetah had no way of teaching her cubs to let the jackals aid their stalks, and one family of jackals is just not enough to create a population of cheetah assistants.

But humans and these unpersecuted Eurasian wolves of the Pleistocene certainly could create these conditions.

I imagine that the earliest wolf-assisted hunts went much like these jackal-cheetah hunts. Wolves are always testing prey to assess weakness. If a large deer species or wild horse is not weak, it will stand and confront the wolves, and in doing so, it would be exposing itself to a spear being thrown in its direction.

If you’ve ever tried a low-carbohydrate diet, you will know that your body will crave fat. Our brains require quite a bit of caloric intake from fat to keep us going, which is one of those very real costs of having such a large brain. Killing ungulates that stood to fight off wolves meant that would target healthy animals in the herds, and healthy animals have more fat for our big brains.

Thus, working together with wolves would give those humans an advantage, and the wolves would be able to get meat with less effort.

So maybe working together with these Ellesmere-like wolves that lived in Eurasia during the Paleolithic made us both more effective predators, and unlike with the cheetah and the black-backed jackals, human intelligence, language, and cultural transmission allowed this cooperation to go on over generations.

Eaton may have stumbled onto the secret of dog domestication. It takes more than the odd population of scavenging canids to lay the foundations for this unusual domestication. Human agency and foresight joined with the simple cooperative nature of the beasts to make it happen.

Posted in hunting, Uncategorized, tagged brook trout, rainbow trout on April 5, 2018|

I caught these trout at Cooper’s Rock this evening.

The one on the bottom is a nice fat brook trout.

Posted in Carnivorans, conservationist, wild dogs, wildlife, tagged Brigantine red fox, piping plovers, red foxes, red knot on April 2, 2018|

New Jersey is a place I think of when I think of a place where animal rights ideology has become quite pernicious. It is a densely-populated state that still has a lot of wild areas still left within its borders, but wildlife management decisions that include lethal control are quite controversial in that state.

For example, in my state of West Virginia, we have plenty of black bears. Black bears are state symbol, and if you go to any gift shop in the state, there will be black bears featured on so many different object. We love our bears, but we also manage them with hunting season.

New Jersey has the same species of bear, and this bear species is one of the few large carnivorans that is experiencing a population increase. Biologists know that hunting a few black bears every year doesn’t harm their populations at all, and in my state, bear tags go to promote bear conservation and to mitigate any issues between people and bears. Hunting these bears also gives the bears a healthy fear of humans, and it is virtually unknown for a bear to attack someone here. New Jersey has had a bear hunt for the past few years, but it has been met with far more controversy there than it ever would be here. Checking stations get protesters, as do wildlife management areas that are open to bear hunting.

Since the bear hunt began, human and bear conflicts have gone down dramatically. The population is thinned out a bit, and the bears learn that people aren’t to be approached. But those potential conservation gains are likely to be erased sooner rather than later.

The animal rights people have become powerful enough in that state that no Democrat can make it through the primaries without pledging to end the bear hunt. The new Democratic governor wants to do away with the bear hunt.

But the bear hunt isn’t the only place where the animal rights people are forcing misguided policy.

A few days ago, I posted a piece about the inherent conflict between animal rights ideology and conservation, and it didn’t take me long to find an article about red foxes in Brigantine, New Jersey. Brigantine is an island off the New Jersey coast.

Like most places in the Mid-Atlantic, it has a healthy population of red foxes, but it also has a nesting shorebird population, which the foxes do endanger. One of the shorebirds that nests on the island is the piping plover, a species that is listed as “near threatened” by the IUCN. Red knot also use the island on their migrations between South America and their Canadian arctic nesting ground. This species is also listed as near threatened, and both New Jersey and Delaware have enacted regulations and programs to protect them.

At Brigantine, people began to discover dead red foxes in the sand dunes, and because red foxes are canids and canids are charismatic. It was speculated that the foxes were poisoned, and the state DEP was asked if the agency had been poisoning foxes there.

The state apparently answered that it had no been poisoning foxes on Brigantine’s beaches. It has been trapping and shooting red foxes.

To me, the state’s management policy makes perfect sense. North American red foxes are in no way endangered or threatened. Their numbers and range have only increased since European settlement, and they are classic mesopredators. Mesopredators are those species of predator whose numbers would normally be checked by larger ones, but when those larger ones are removed, the smaller predators have population increases. These increased numbers of smaller predators wind up harming their own prey populations.

This phenomenon is called “mesopredator release.” It is an important hypothesis that is only now starting to gain traction in wildlife management science. What it essentially means is that without larger predators to check the population of the smaller ones, it is important to have some level of controls on these mesopredators to protect biodiversity.

Animal rights ideology refuses to consider these issues. In fact, the article I found about these Brigantine foxes is entitled “These adorable foxes are being shot to death by the state.” The article title is clickbaitish, because the journalist interviewed a spokesperson at the DEP, who clearly explained why the fox controls were implemented.

The trappers who took the foxes probably should have come up with a better way of disposing of the bodies. One should also keep in mind that New Jersey is one of the few states that has totally banned foot-hold traps for private use, so any kind of trapping is going to be controversial in that state. So the state trappers should have been much more careful.

But I doubt that this will be the end of the story. The foxes have been named “unofficial mascots” of Brigantine, and it won’t be long before politicians hear about the complaints. The fox trapping program will probably be be pared back or abandoned altogether.

And the piping plover and red knot will not find Brigantine such a nice place to be.

And so the fox lovers force their ideology onto wildlife managers, and the protection of these near threatened species becomes so much harder.

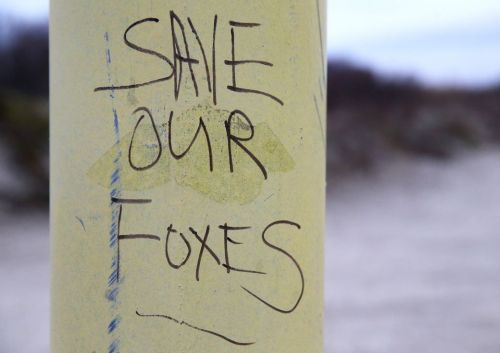

This sign was posted in 2016 after the first dead foxes were found:

But I don’t think many people will be posting “Save Our Piping Plovers.” Most people don’t know what a piping plover is, but red foxes are well-known.

They get their special status because they are closely related to dogs, and people find it easy to transfer feelings about their own dogs onto these animals.

This makes sense from a human perspective, but it makes very little sense in terms of ecological understanding.

And it makes little sense for the foxes, which often die by car strikes and sarcoptic mange, especially when their population densities become too high.

Death by a trapper’s gun is far more humane than mange. The traps used are mostly off-set jawed ones, ones that cannot cut the fox as it is held. The trap is little more than a handcuff that grabs it by the foot and holds it. The traps are checked at least once a day, and the fox dies with a simple shot to the head, which kills it instantly.

And the fox numbers are reduced, and the island can hold rare shorebirds better than it could before.

In trying to make a better world for wildlife, we sometimes have to kill. This is an unpleasant truth.

And this truth becomes more unpleasant when we start conflating animal rights issues with conservation issues. Yes, we should make sure that animals are treated humanely, but we cannot make the world safe for wildlife without controlling mesopredators and invasive species.

I think that most of the fox lovers do care about wildlife, but they are so removed from wildlife issues on a grand scale that it becomes harder to understand why lethal methods sometimes must be used.

My guess is these people like seeing foxes when they are at the beach and don’t really think about these issues any more than that.

It is not just the wildlife exploiters and polluters that conservationists have to worry about. The animal lovers who extend too much animal rights ideology into conservation issues are a major problem as well.

And sadly, they are often the people that are the hardest to convince that something must be changed.

I don’t have a good answer for this problem, but it is one that conservationists must consider carefully as the future turns more and more in the favor of animal rights ideology.

Posted in wolves, working dogs, tagged Kazakh tazi, Steppe wolf, tazi, wolf hybrid, wolf. dog, wolfdog on April 2, 2018|

This image appeared on a Kazakh instagram account.

The wolf appears to be a steppe wolf (Canis lupus campestris). In Kazakhstan, people keep wolves as pets and “guard dogs” fairly often, and according to Stephen Bodio, they are obsessed with wolves.

The dog is a tazi, a sighthound of the general saluki breed complex, that has quite a few wolf-like characteristics. The breed is usually monestrus, like a wolf, coyote, or a basenji, and females engage in social suppression of estrus and sometimes kill puppies that are born to lower ranking bitches.

I wonder if the wolf-like traits of this breed are somehow reinforced by occasionally crossings with captive and wandering wolves like this. As far as I know, no one has really looked into the genetics of the Kazakh tazi, but it is an unusual dog that lives in a society with a very strong tradition of keeping captive wolves.

We know that gene flows between Eurasian wolves and dogs is much higher than we initially imagined, but I don’t know if anyone is looking at breeds like these for signs of hybridization. The only study I’ve seen looked at livestock guardian dogs from the Caucasus, and it found quite a bit of gene flow-– and it was mostly unintentional.

It would be interesting to know exactly how much wolf is in Kazakh tazis. I would be shocked to learn that they had no wolf ancestry.

I seriously doubt that this is the only time a captive steppe wolf and a tazi were found in this position.