Stolen from Pai on Facebook:

Archive for December, 2011

Pelicans and flying devil rays

Posted in birds, wildlife, tagged devil rays on December 31, 2011| 1 Comment »

Was the Hare Indian dog a domesticated coyote?

Posted in dog breeds, dog domestication, working dogs, tagged coyote, domesticated coyote, Hare Indian dog, Native American dog, Tahltan bear dog on December 31, 2011| 19 Comments »

Scottish naval surgeon and naturalist Sir John Richardson was the first document a peculiar hunting dog among the Slavey or Hare people of Northern Canada. This particular dog was much smaller than the typical qimmiq or “Eskimo dog” that was found throughout the region and was also often used to hunt. It was also quite different from the qimmiq and the Newfoundland-derived dogs that Europeans often kept for hauling loads. From Richardson’s description, “the Hare Indian dog” was quite an unusual animal.

Richardson’s entry on the Hare Indian dog appears in his Fauna Boreali-americana (1829):

The Hare Indian Dog has a mild countenance, with, at times, an expression of demureness. It has a small head, slender muzzle; erect, thickish ears; somewhat oblique eyes; rather slender legs, and a broad hairy foot, with a bushy tail, which it usually carries curled over its right hip. It is covered with long hair, particularly about the shoulders, and at the roots of the hair, both on the body and tail, there is a thick wool. The hair on the top of the head is long, and on the posterior part of the cheek it is not only long, but being also directed backwards, it gives the animal, when the fur is in prime order, the appearance of having a ruff round the neck. Its face, muzzle, belly, and legs, are of a pure white colour, and there is a white central line passing over the crown of the head and the occiput. The anterior surface of the ear is white, the posterior yellowish-gray or fawn-colour. The end of the nose, the eyelashes, the roof of the mouth, and part of the gums, are black. There is a dark patch over the eye. On the back and sides there are larger patches of dark blackish-gray or lead-colour mixed with fawn-colour and white, not definite in form, but running into each other. The tail is bushy, white beneath and at the tip. The feet are covered with hair which almost conceals the claws. Some long hairs between the toes project over the soles, but there are naked callous protuberances at the root of the toes and on the soles, even in the winter time, as in all the wolves described in the preceding pages. The American foxes, on the contrary, have the whole of their soles densely covered with hair in the winter. Its ears are proportion ably nearer each other than those of the Esquimaux dog.

The size of the Hare Indian Dog is inferior to that of the prairie wolf [coyote], but rather exceeds that of the red American fox. Its resemblance, however, to the former is so great, that, on comparing live specimens, I could detect no marked difference in form, (except the smallness of its cranium,) nor in the fineness of the fur, and arrangement of its spots of colour. The length of the fur on the neck, back part of the cheeks, and top of the head, was the same in both species. It, in fact, bears the same relation to the prairie wolf that the Esquimaux Dog does to the great gray wolf. It is not, however, a breed that is cultivated in the districts frequented by the prairie wolf, being now confined to the northern tribes, who have been taught the use of fire-arms within a very few years. Before that weapon was introduced by the fur-traders, a dog, so well calculated by the lightness of its body and the breadth of its paws, for passing over the snow, must have been invaluable for running down game, and it is reasonable to conclude that it was then generally spread amongst the Indian tribes north of the Great Lakes.

The Hare Indian Dog is very playful, has an affectionate disposition, and is soon gained by kindness. It is not, however, very docile, and dislikes confinement of every kind. It is very fond of being caressed, rubs its back against the hand like a cat, and soon makes an acquaintance with a stranger. Like a wild animal, it is very mindful of an injury, nor does it, like a spaniel, crouch under the lash; but if it is conscious of having deserved punishment, it will hover round the tent of its master the whole day, without coming within his reach, even when he calls it. Its howl, when hurt or afraid, is that of the wolf; but when it sees any unusual object, it makes a singular attempt at barking, commencing by a kind of growl, which is not, however, unpleasant, and ending in a prolonged howl. Its voice is very much like that of the prairie wolf . The larger dogs, which we had for draught at Fort Franklin, and which were of the mongrel breed in common use at the furposts, used to pursue the Hare Indian Dogs for the purpose of devouring them ; but the latter far outstripped them in speed, and easily made their escape. A young puppy, which I purchased from the Hare Indians, became greatly attached to me, and when about seven months old ran on the snow by the side of my sledge for nine hundred miles, without suffering from fatigue. During this march it frequently, of its own accord, carried a small twig or one of my mittens for a mile or two ; but, although very gentle in its manners, it shewed little aptitude in learning any of the arts which the Newfoundland dogs so speedily acquire, of fetching and carrying when ordered. This Dog was killed and eaten by an Indian, on the Saskatchewan, who pretended that he mistook it for a fox (pg. 79-80).

The Hare Indian dog sounds very different from most domestic dogs, but the fact that dog’s bark and howl behavior sounds very much like a coyote. I have never known a dog that sounded like a coyote when it howled. Coyotes make a very distinct how that no dog can quite mimic.

The fact that other dogs don’t seem to treat it as a conspecific also points to the possibility of it being a domesticated coyote. Large dogs will run down coyotes and kill them, especially if they are running in a pack. Foxhounds are regularly used for this purpose in this part of the country. Around here, the hounds just chased red foxes. The object never was to catch them, but when the hounds were used against coyotes, the coyotes developed a nasty habit of standing to fight the dogs. A couple of foxhounds can make short work of a coyote that decides to make a stand in this fashion.

Further, I have noted that every golden retriever I’ve known has generally loved being around other dogs, even if these dogs were strangers. However, I’ve never known a golden retriever that didn’t have a passionate hatred for coyotes. In fact, I’ve never met a dog that didn’t detest everything about a coyote, whether it liked other dogs or not.

Now, these dogs that were kept at fur trading posts were kept in sled teams. Occasionally, sled dogs were fed dead sled dogs, but I don’t think there is much evidence of sled dogs seeking out conspecifics for predation. Wolves definitely do this, but if sled dogs were like this, they would be next to impossible to keep in teams.

Wolves, of course, do often kill coyotes whenever they get a chance, so maybe Richardson’s analogy also makes sense in this regard.

The only problem with the Hare Indian dog being a coyote is that it existed far to the north of where coyotes ranged in historical times.

However, they may have lived to the north in prehistoric times, or the Slavey might have procured them from trading with peoples to the south.

If the Hare Indian dog had been a domesticated form of coyote, it would not have been the only “dog” in the Americas to derive from an ancestor other than the wolf. The natives of Tierra del Fuego kept a dog that was found to be a domesticated form of the culpeo. Culpeos (Lycalopex culpaeus) are South American “wolf foxes” that superficially resemble small coyotes. According to Charles Darwin, the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego kept these foxes to hunt otters. However, he could have been confusing the Spanish word “nutria,” which actually does mean otter, to refer to the coypu, which also referred to as a nutria. Charles Hamilton Smith thought these domesticated culpeos were quite useless, only coming to villages to scavenge.

John Bradshaw notes that there is some evidence of golden jackal domestication at Neolithic site in what is now Turkey, and a Pre- Natufian red fox burial in Jordan shows that some people were trying to tame that species as well. (The assumptions behind that fox study are a bit off. The earliest domestic dog remains are older than this Pre-Natufian period.)

It would not surprise me if the Hare Indian dog did turn out to be a domesticated coyote.

However, this breed went extinct. Some people claim that there are lines of Native American dog that have this ancestry, but it seems awfully dubious.

The real reason why the little hunting “dog” of the Slavey went extinct are very simple. Richardson’s text alludes to the factors that led to its eventual extinction, and these same factors almost perfectly parallel the extinction of the Tahltan bear dog, which was like a larger northern variant of the chihuahua. It may have been related to the techichi, which is the purported ancestor of the chihuahua.

Mary Elizabeth Thurston in her The Lost History of the Canine Race writes about Leslie Kopas, a Canadian author who tracked down the last Tahltan bear dogs and wrote about the factors leading to their extinction.

Like the Hare Indian dog, the Tahltans were used to hunt game. However, when rifles arrived with European traders, the dogs became less useful. The Tahltans were better able to shoot large game without the assistance of a dogs, and they were also able to feed large packs of sled dogs. Sled dogs would kill Tahltan bear dogs if they caught them. Sled dogs were of greater importance than the bear dogs, and the bear dogs soon became extinct as the packs of sled dogs killed them. Thurston quotes Kopas, “If the snowmobile had been invented before the rifle, the sled dogs would have disappeared first, and the Tahl Tan Bear Dog might have survived’ (pg. 167).

From Richardson’s account, something similar may have happened to the Hare Indian dog, even though other sources claim that they were absorbed into the mongrel sled dog population. I am more than somewhat skeptical.

I have also read that there are dogs from Native American villages today strongly resemble Hare Indian dogs, but many dogs from reservations and settlements have this coyote-esque appearance.

I’ve not heard of any of these dogs bark-howling like a coyote, unless they were hybrids with coyotes. Most Native American dogs aren’t.

I know of no remains of Hare Indian dogs anywhere, so we may never get an answer to the question of its identity.

It sounds very much like a domesticated coyote, but we need DNA analysis in order to fine out its exact origin.

I guess it’s just one of those mysteries that will never be answered.

William Stratton and the brindle retriever

Posted in Labrador retriever, Newfoundland, Retriever history, St. John's Water Dog, tagged Cao de Castro Laboreiro, Labrador, Labrador dog, Labrador retriever, Newfoundland, St. John's Water Dog on December 30, 2011| 23 Comments »

This portrait by Edmund Havell was painted around the year 1840.

It is called “William Stratton, Head Keeper to Sir John Cope of Bramshill Park, Hampshire.”

The original copy no longer exists.

For some reason, it was displayed at the British Embassy in Tripoli.

Earlier this year, when Libya was in throes of a bitter civil war. The United States, Britain, France, and Italy were engaged in supporting the rebels against Col. Gaddafi with air strikes. In a demonstration of their rage against the West, Gaddafi’s supporters stormed and looted the British embassy. They took the fine works of art out of the embassy, and it is believed that they were burned.

The Sir John Cope who employed William Stratton as his keeper was not the famous military commander who lost to the Jacobites at Prestonpans in 1745. This Sir John Cope assume the title in 1812, but he was part of the same Cope family that had owned Bramshill Park since 1700.

The dog is of great interest to retriever history, for here we have an unequivocal example of a red brindle retriever.

Brindle still pops up in Labrador and Chesapeake Bay retrievers today, and it is masked by the e/e mutation in golden retrievers. The only way one can see it in golden retrievers is if a golden with a e/e masking brindle is bred to another breed. (Like these golden retriever/Malinois crosses.) Most golden retrievers are e/e masking dominant black, but black and tan, brindle, and sable can be masked.

This particular dog strongly resembles a Cão de Castro Laboreiro. It is often suggested that the St. John’s water dog or early Labrador is partially derived from this dog. Stonehenge wrote that brindling on an English retriever would be indicative of its “Labrador” heritage:

An English retriever, whether smooth or curly-coated, should be black or black-and-tan, or black with tabby or brindled legs, the brindled legs being indicative of the Labrador origin. We give the preference, from experience, to the flat-coated or short-coated small St. John’s or Labrador breed. These breeds we believe to be identical. The small St. John’s has marvellous intelligence, a great aptitude for learning to carry, a soft mouth, great strength, and he is a good swimmer. If there is any cross at all in this breed it should be the setter cross (pg. 89).

(Note that there is a definite reference to the St. John’s breed having long hair. “Flat-coated” means long haired in retriever parlance.)

Charles Eley in his The History of Retrievers (1921) wrote that with wavy/flat-coated retrievers that “[t]he early specimens had frequently shown tan and brindle.”

In those accounts, the retrievers were only brindle at tan points or on the legs.

This dog is entirely red brindle.

This brindle dog could have been called a Newfoundland, a Labrador, a St. John’s water dog or St. John’s dog, or a wavy-coated retriever, depending upon the context. Because the painting dates to about 1840, it more than likely would have been called Labrador or Newfoundland.

These dogs were developed from stock that belonged to various people living in Newfoundland. One should never discount that the mainstay of English, British, and Irish settlers brought dogs from those countries. However, there were several nations that fished off Newfoundland– most notably, the Portuguese. Most people know that the Portuguese were among the first Europeans to visit the island, and the place called Labrador was actually land that the Portuguese crown granted to a sailor who explored this part of the world in the fifteenth century.

Fishing off the Grand Banks was a stable of the Portuguese economy well into the twentieth century.

The tendency in many official retriever histories was to ignore the possibility that Iberian breeds could have played a role in the founding of the St. John’s water dog. Richard Wolters dismissed the possibility that the Portuguese water dog could have played some role in developing the St. John’s breed, simply because the official concession on the Grand Banks gave the Portuguese different fishing grounds from the British and Irish fishermen.

The problem with this dismissal is that from at least the eighteenth century, English and Irish settlers were living in Newfoundland– in defiance of a law passed in parliament that forbid permanent settlement on the island. Many of these people were pressed into service with the British navy– freed from jails and workhouses, where they may have been sent for poaching on the great hunting estates. These sailors– almost all of them men– lived in defiance of the law, and they called themselves “the Masterless Men.”

These Masterless Men likely wouldn’t have paid any attention to any maritime laws, and they likely occasionally relied upon the Portuguese and sailors from other nations to gain access to new goods.

I don’t see why such people would not have been able to procure Portuguese water dogs, which act very much like retrievers and worked on the Portuguese fleets in almost the exact same fashion as the St. John’s water once did.

I also don’t see why the Cão de Castro Laboreiro or something very similar to it couldn’t have been brought over with the Portuguese.

Cão de Castro Laboreiro is a rustic farm dog from northern Portugal. It is from the village of Castro Laborerio, which it was developed to guard cattle and other livestock from wolves. It can handle cold conditions quite well.

There is a very similar brindle dog on the Azores, Cão de Fila de São Miguel. It’s normally cropped and docked and looks quite fierce, but when undocked, it is very similar. It has a different mtDNA sequence, but since we’re talking about dogs that may have come from the same generalized landrace– and dog from the Azores represents an insular population– it might be possible that these dogs are more closely related than the mtDNA analysis might suggest.

Cão de Castro Laboreiro. This dog is very similar to the retriever in the painting by Edmund Havell. They also come in yellow, and the yellow ones really look like Labradors.

My guess is the rough cattle dog-type from northern Portugal would have been an asset in Newfoundland, which was full of black and polar bears (which were called “water bears.”) Breed this sort of dog with some working English cur dogs, water spaniels, Portuguese, French, Spanish, and English water dogs (poodle-type dogs), and the odd retrieving Native American dog from the mainland. Then allow a rigorous selection from that melange of canines for function and for ability, and you likely get the formula that gave us the St. John’s water dog.

It is even possible that the name “Labrador” that is used to refer to these dogs comes from a misunderstanding of the Portuguese word “Laboreiro.” The St. John’s breed was developed on the island of Newfoundland and then was taken to Labrador. It was not actually developed in Labrador at all.

And the actually modern Labrador retriever, which is always said to be the oldest of retrievers, came into its current form somewhat more recently than the strains of retriever that became golden retrievers. They were developed into their current form in Britain–mainly by the Dukes of Buccleuch in Scotland. Labrador retriever as we know it today is no more Canadian than the other large retrievers are. They all descend from the St. John’s water dog, but the modern Labrador is not the same thing as the St. John’s water dog. (The Nova Scotia duck-tolling retriever actually is Canadian, but it’s not primarily derived from the St. John’s water dog as the others are. It’s actually primarily collie.)

The real problem that some people have with the Cão de Castro Laboreiro being an ancestor of retrievers is the temperament of the Cão is much sharper than any of the retrievers.

But that assumes that all retrievers are as docile as Labrador and golden retrievers and that their ancestors were just as nice. It’s true that the St. John’s water dogs that survived on Newfoundland into the twentieth century were very nice friendly dogs.

But they weren’t always this way. Col. Peter Hawker was British sportsman who was the first person to write about using the St. John’s water dog as a retriever in the United Kingdom. In his Instructions to Young Sportsmen (1824), he describes the temperament of the dogs very differently from what one might expect:

Newfoundland [St. John’s water] dogs are so expert and savage, when fighting, that they generally contrive to seize some vital part, and often do a serious injury to their antagonist. I should, therefore, mention, that the only way to get them immediately off is to put a rope, or handkerchief, round their necks, and keep tightening it, by which means their breath will be gone, and they will be instantly choked from their hold (pg. 256).

That’s a very different temperament from what is normally expected of a retriever.

Over time, these dogs were bred to be much more docile. However, two dogs of this ancestry retain their more aggressive natures. Shooting estates required dogs that were friendlier and more docile, as did the development of retriever trials.

And these two retrievers are likely the earliest offshoots of the St. John’s water dog– the Chesapeake Bay retriever and the curly. These two dogs are known for having a somewhat sharper edge than the other retrievers, although they are not nearly as extreme as the Cão de Castro Laboreiro.

Now, this brindle color could have come from a variety of places. There are lots of brindle dogs from England that could have been crossed in.

However, the similarities between the Cão de Castro Laboreiro and the retriever standing with William Stratton are quite striking.

Of course, we do need a DNA analysis to find out if this possibility is more than a striking resemblance.

Black serval

Posted in Carnivorans, wildlife, tagged black serval, melanistic serval, serval on December 29, 2011| 9 Comments »

Caracal vs. Hyenas

Posted in wildlife, tagged Caracal, Spotted Hyena, spotted hyenas on December 29, 2011|

Charlie, Cammie, and Rhodie

Posted in Charlie, English shepherd, Family, tagged English Shepherd, Jack Russell terriers on December 29, 2011|

Asleep on the couch in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Charlie the English shepherd belongs to my cousin Laura Atkinson in Georgia.

He’s a good dog.

And the JRT pups are, too– when they are asleep.

A Newfoundland-type travois dog

Posted in Newfoundland, St. John's Water Dog, working dogs, tagged Newfoundland dog, St. John's Water Dog, travois dog on December 29, 2011| 11 Comments »

This is a Lakota woman and her travois dog.

This photo was taken on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

I don’t know the date on which this was taken, but her dog is not a traditional travois dog.

It appears to be heavily derived from the Newfoundland/St. John’s water dog type.

These dogs were brought into the interior of North America by fur traders, and the Native Americans adopted them as working animals.

They bred with the indigenous dog, and because they were more resistant to disease and were not shot because settlers mistook them wolves or coyotes, they largely replaced the travois dog type.

This dog looks almost like a golden retriever that has been hooked up to a travois.

The alco and “the carrier dog of the Indians”

Posted in dog breeds, wild dogs, tagged alco, Hare Indian dog, Native American dogs, Prairie dog, Techichi on December 29, 2011| 4 Comments »

Believe it or not, but this image is of two domestic dogs.

“WTF?” you say.

Yep.

This image comes from The Natural History of Dogs (1840) by Charles Hamilton Smith and William Jardine.

On the left is an alco. If one reads the description of the alco, it is a small dog of Meso-America, probably something like what we think the ancestor of the chihuahua was like. The authors mention these dogs living as feral animals, which is currently a de rigueur comment on all official histories of the chihuahua. The only difference I can see is that alco is described as looking like a Newfoundland puppy, which means they were likely almost always drop-eared. These little parti-colored dogs were known in Mexico from the early days. Some texts, like Mary Elizabeth Thurston’s The Lost History of the Canine Race, calls them “techichi.” Techichi are popularly known as the ancestor of the chihuahua, but the mummified dog in Thurston’s book that is said to have been a techichi is long-haired and black and white– and has floppy ears. It is a myth that all dogs owned by Native Americans before the arrival of Columbus were all large and wolf-like. Some were quite small, and some were brachycephalic.

The dog on the right is much screwier.

Look at the head.

It looks like some kind of rodent.

I think the reason why this animal looks so bizarre is that the authors rather haphazardly conflate several different things called dog, including something that isn’t a dog at all. The engraver who produced the image was William Home Lizars, who lived in Scotland. I can’t find any evidence that he was ever outside of Europe.

The authors, however, likely confused him about what this animal looked like in their texts.

The authors came across a tawny dog in what I am guessing is San Juan del Rio in the state of Querétaro in central Mexico. The authors call this dog a “techichi,” which Thurston conflates with the alco. This conflation may or may not be correct, but it is closer to being correct than conflation that Hamilton Smith and Jardine produce.

We have seen only one individual of this race, by the Indians called Techichi. It was a long-backed heavy looking animal, with a terrier’s mouth, tail, and colours; but the hair was scantier and smoother, and the ears were cropped. It is likely that the specimen seen by us at Rio de San Juan was of the same race as the Techichi described by Fernandez.

To this race belongs the Carrier Indian Dog observed by Dr. Richardson, and described by him, in a letter we had the pleasure of receiving, as having a long body, with legs comparatively short, but not bent, and short (not woolly) hair (pg. 156).

Richardson’s dog was probably the Hare Indian dog, which was much smaller than the travois dog of the Plains Indians. This dog was described by Sir John Richardson, and he described the dog as being like a small black and white coyote. The dogs were used for hunting, and he extolled its virtues as a hard running dog. These dogs were not used for hauling, but they would carry a twig or mitten in their mouths as they ran– which is where Hamilton Smith and Jardine get the “carrier dog” name. Richardson thought the breed was a domesticated form of coyote.

It may have been exactly that, but the breed has since gone extinct. And no remains have been found for modern science to examine.

Now, Hamilton Smith and Jardine start going down several rabbit holes in their discussion of Native American dogs. They mention William Bartram’s black wolf dog, which Bartram encountered guarding herds of Seminole ponies. They also talk about a black wolf-like dog from Canada that was very much like the old Newfoundland (St. John’s water dog) in temperament.

And then the authors mention Maximilian von Wied’s encounter with wolfish dogs on the Great Plains, which he thought were derived from wolves. The authors disagree with Maximilian, claiming that the dogs derive from”Caygotte” (coyote), a view they shared with Richardson. Of course, the dogs on the Plains were larger than the Hare Indian dogs, and they were used primarily for hauling. Maximilian would also talk about these dog mingling with the large wolves of the Great Plains, which leads one to believe that if they had any wolf in them, it was the Holarctic wolf and not the coyote.

If Hamilton Smith and Jardine had left their discussion with the discussion of Caygotte as the ancestor of the Native American dogs, it would not have been confusing, but in the next sentence, the authors posit that “[T]here [is no] reason for rejecting the prairie dog (Lyciscus latrans) as one of those who have contributed to furnish breeds of original American dogs” (pg. 156).

Now, if you read a little deeper into the Hamilton Smith and Jardine text, “Lyciscan dogs” are what we would call the coyote, which the authors divide into the Caygotte and the North American prairie wolf. The prairie wolf gets the name “Lyciscus latrans,” which we now call Canis latrans– the coyote. However, the authors use Caygotte, the supposed Basque name for this dog in Mexico, to extend not only to what we would call the Mexican and Central American coyote but to several species of South American wild dog, some of which might be nothing more than wolfish variants of the domestic dog. The authors then enter an aside which posits that a legendary dog in India, which is said to have been a hybrid between a dog and a tiger, is actually a Lyscican dog– an Old World variant of this coyote tribe. I guess the dog and tiger hybrid suggestion was too silly for them! The South American “Caygotte” is probably a reference to the culpeo (Lycalopex culpaeus), which superficially looks like a small coyote, but it is actally part of the South American “fox” genus (Lycalopex— “the wolf foxes.”).

If the authors had been more careful in their wording of the common name for the supposed ancestor of the ‘”carrier dog/Techichi” and called it a “prairie wolf,” I don’t think Lizars would have produced such a bizarre image.

Hamilton Smith and Jardine use the word “prairie dog” instead of “praire wolf,” but it is obvious the authors mean prairie wolf. They use the scientific name Lyciscus latrans.

William Home Lizars was not a scientist, so my guess is that when he saw that these animals looked like they might be derived from a prairie dog, he looked up a prairie dog.

A prairie dog is a rodent– a type of ground squirrel. They native to the Great Plains of North America from South Central Canada to Northern Mexico. They live in vast colonies that include extensive burrows, which we call “prairie dog towns.” Whenever, a dangerous animal appears on the scene, one prairie dog will warn the others through barking– well, it kind of sounds like barking– and that’s how they got this name.

My guess is that when Lizars saw prairie dog as possible ancestor of the techichi/carrier dog, he looked up the prairie dog. He saw the squirrel, and he also saw that the authors mention it as being tawny. Prairie dogs are tawny squirrels.

So he made the carrier dog look like a hybrid between a chihuahua and a prairie dog. Not only is a prairie dog long-backed and tawny, it looks like its ears have been cropped.

Now that’s about as fanciful as the tiger dog hybrids!

One can see what sort of conflations people could produce from having very imperfect information about natural history.

The image at the top of this post comes from conflating the techichi with the Hare Indian dog and the other wolf-like dogs of the Native Americans. The supposition that some of these dogs were derived from coyotes or “prairie wolves” became mixed up with the prairie dog.

And the result is an image of a sort of chimerical animal that would probably scare the living daylights out of anyone who happened to encounter it.

Did Cheetah die at the age of 80?

Posted in Absolute Piffle, wildlife, tagged cheetah, Cheetah the Chimp on December 29, 2011| 13 Comments »

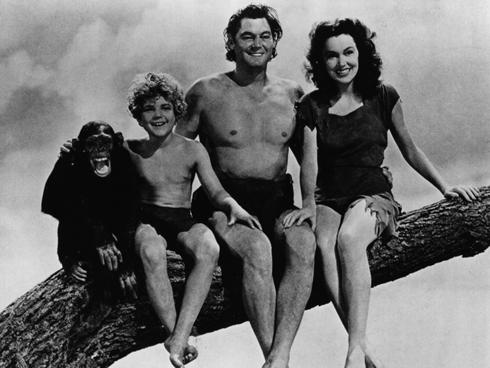

A few days ago, I received this news in my inbox: The chimp who played “Cheetah” in the Tarzan movies died on Christmas Eve at the age of 80.

I didn’t cover it for one really big reason.

I’ve never heard of chimp making it to 80. I’ve heard of them living into their 70’s. 80 is possible, but I would have thought that more notice would have been paid to Cheetah’s really advanced age.

Well, it turns out that there is no proof that the chimp that died on Christmas Eve was Cheetah.

From ABC News:

A Florida animal sanctuary says Cheetah, the chimpanzee sidekick in the Tarzan movies of the early 1930s, has died at 80. But other accounts call that claim into question.

Debbie Cobb, outreach director at the Suncoast Primate Sanctuary in Palm Harbor, said Wednesday that her grandparents acquired Cheetah around 1960 from “Tarzan” star Johnny Weissmuller and that the chimp appeared in Tarzan films between 1932 and 1934. During that period, Weissmuller made “Tarzan the Ape Man” and “Tarzan and His Mate.”

But Cobb offered no documentation, saying it was destroyed in a 1995 fire.

Also, some Hollywood accounts indicate a chimpanzee by the name of Jiggs or Mr. Jiggs played Cheetah alongside Weissmuller early on and died in 1938.

In addition, an 80-year-old chimpanzee would be extraordinarily old, perhaps the oldest ever known. According to many experts and Save the Chimps, another Florida sanctuary, chimpanzees in captivity generally live to between 40 and 60, though Lion Country Safari in Loxahatchee, Fla., says it has one that is around 73.

A similar claim about another chimpanzee that supposedly played second banana to Weissmuller was debunked in 2008 in a Washington Post story.

Writer R.D. Rosen discovered that the primate, which lived in Palm Springs, Calif., was born around 1960, meaning it wasn’t oldest enough to have been in the Tarzan movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age that starred Olympic swimming star Weissmuller as the vine-swinging, loincloth-wearing Ape Man and Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane.

While a number of chimpanzees played the sidekick role in the Tarzan movies of the 1930s and ’40s, Rosen said in an email Wednesday that this latest purported Cheetah looks like a “business-boosting impostor as well.”

“I’m afraid any chimp who actually shared a soundstage with Weissmuller and O’Sullivan is long gone,” Rosen said.

Cobb said Cheetah died Dec. 24 of kidney failure and was cremated.

“Unfortunately, there was a fire in ’95 in which a lot of that documentation burned up,” Cobb said. “I’m 51 and I’ve known him for 51 years. My first remembrance of him coming here was when I was actually 5, and I’ve known him since then, and he was a full-grown chimp then.”

Film historian and Turner Classic Movies host Robert Osbourne said the Cheetah character “was one of the things people loved about the Tarzan movies because he made people laugh. He was always a regular fun part of the movies.”

In his time, the Cheetah character was as popular as Rin Tin Tin or Asta, the dog from the “Thin Man” movies, Osbourne said.

“He was a major star,” he said.

At the animal sanctuary, Cheetah was outgoing, loved finger painting and liked to see people laugh, Cobb said. But he could also be ill-tempered. Cobb said that when the chimp didn’t like what was going on, he would fling feces and other objects.

Another reason why I was skeptical of the story is that the CNN reporting of the death claimed that Cheetah liked listening to contemporary Christian music.

Chimps are highly intelligent animals.

No intelligent animal would listen to that crap on purpose.

Identify the species

Posted in Carnivorans, Identify the species on December 29, 2011| 7 Comments »